The **Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)** is the Federal Reserve System's pivotal body for setting U.S. monetary policy, steering the economy toward Congress's dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability.[1][2][3]

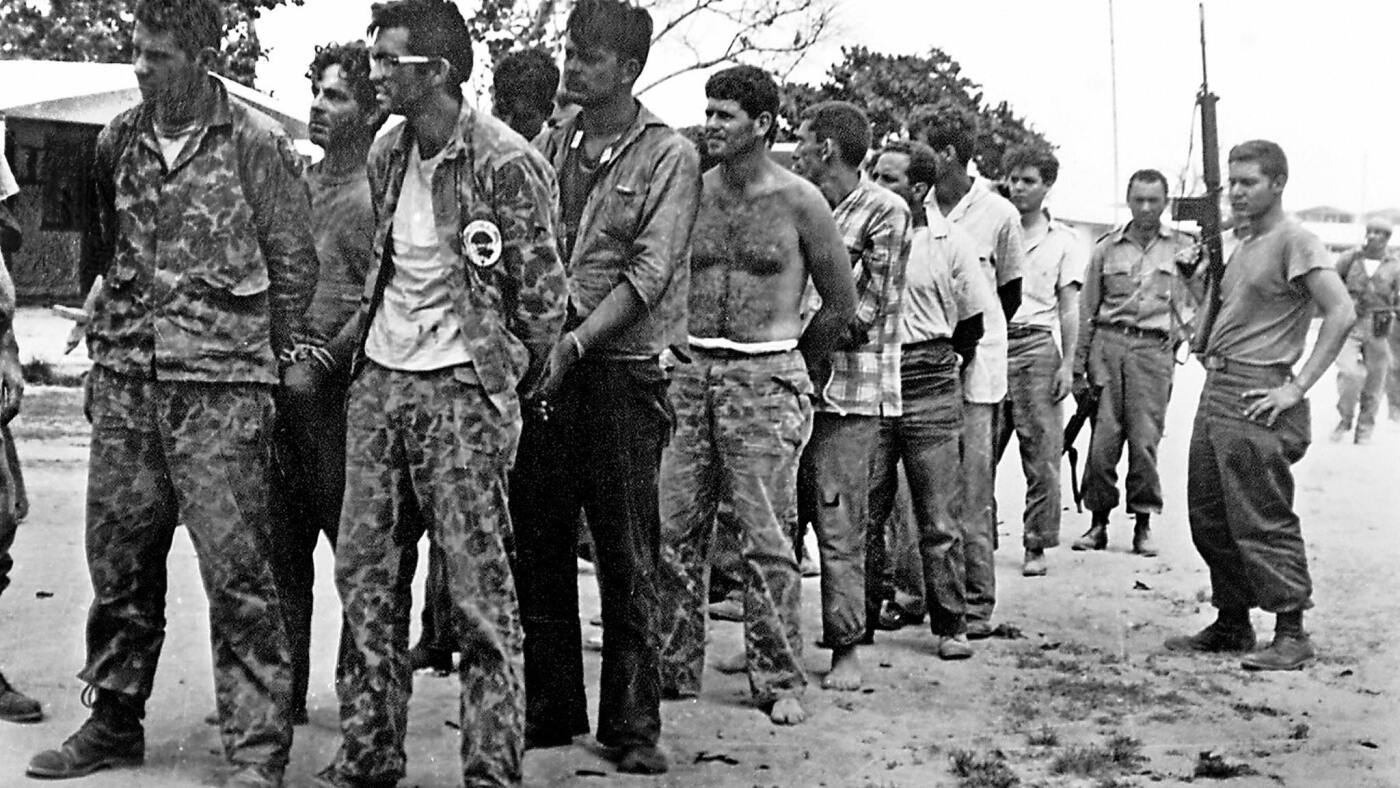

Established through the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 and formalized by the Banking Act of 1935, the FOMC evolved from earlier uncoordinated efforts by the twelve Federal Reserve Banks. Pre-1933, banks conducted open market operations separately or via groups like the 1923 Open Market Investment Committee, but the modern FOMC launched in March 1936 under Chairman Marriner Eccles, centralizing decisions on open market operations that influence the federal funds rate, asset holdings, and public communications.[1][5]

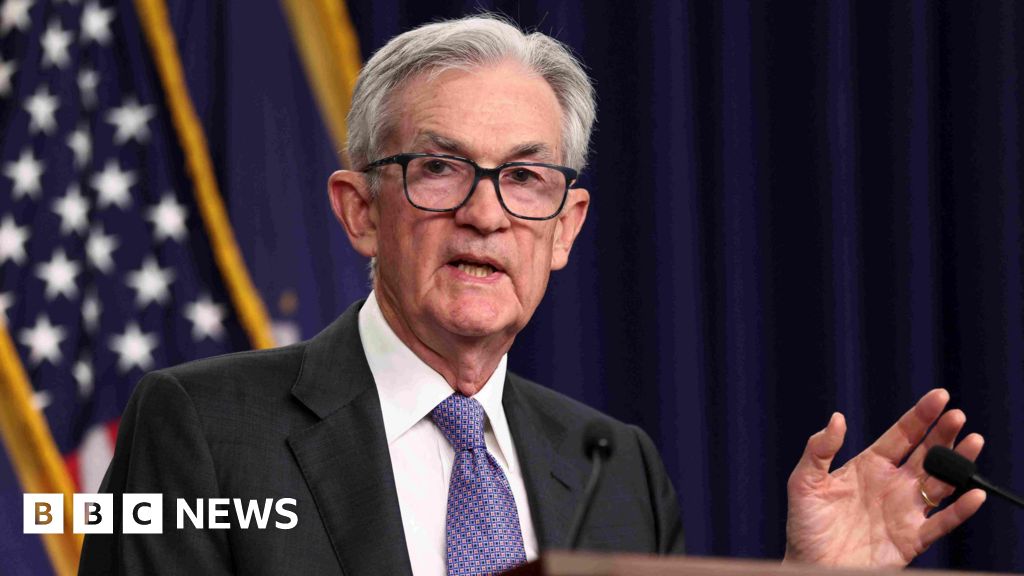

Comprising **12 voting members**—seven Board of Governors, the New York Fed president (permanent), and four rotating Reserve Bank presidents—the group convenes eight times yearly, roughly every six weeks, to dissect economic data, financial markets, and forecasts from Fed economists. Non-voting presidents contribute insights, culminating in policy votes on tools like open market operations (the FOMC's domain), discount rates, and reserve requirements.[2][3][4][5] Post-meeting, statements, minutes (released after three weeks), and chair press briefings (four times yearly with economic projections) amplify transparency.[6]

Key achievements include navigating crises: since 2008, the FOMC pioneered large-scale asset purchases (quantitative easing) to slash long-term rates, bolstering recovery amid recessions.[5] Its actions ripple through markets, swaying interest rates, credit, business investment, and household spending—making FOMC announcements among finance's most watched events.[3][6]

Today, the FOMC remains robust, adapting tools to tame inflation or spur growth amid evolving challenges like tech-driven disruptions and global shocks. Its rigorous, data-fueled deliberations underscor