Japan Hikes Rates to 0.75%: BoJ Signals Policy Normalization

Japan's Bold Rate Hike to 0.75%

Japan's central bank has raised its key short-term interest rate to 0.75%, the highest since 1995, in a unanimous December decision amid persistent inflation pressures[1][2]. This 25 basis point increase from 0.50% marks the second hike this year, signaling a cautious exit from decades of ultra-loose policy as underlying CPI inflation steadily approaches the 2% target[2]. New Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi faces the challenge of taming price rises while preserving affordable borrowing for government debt.

Driving Forces Behind the Move

Firms are passing wage gains to prices, with solid increases this year likely to persist into 2026, bolstering inflation momentum[2]. Real rates remain deeply negative, ensuring accommodative conditions support economic activity despite the tightening[1][2]. Uncertainties like U.S. trade policies have eased, raising confidence in the bank's baseline scenario for stable 2% inflation[2].

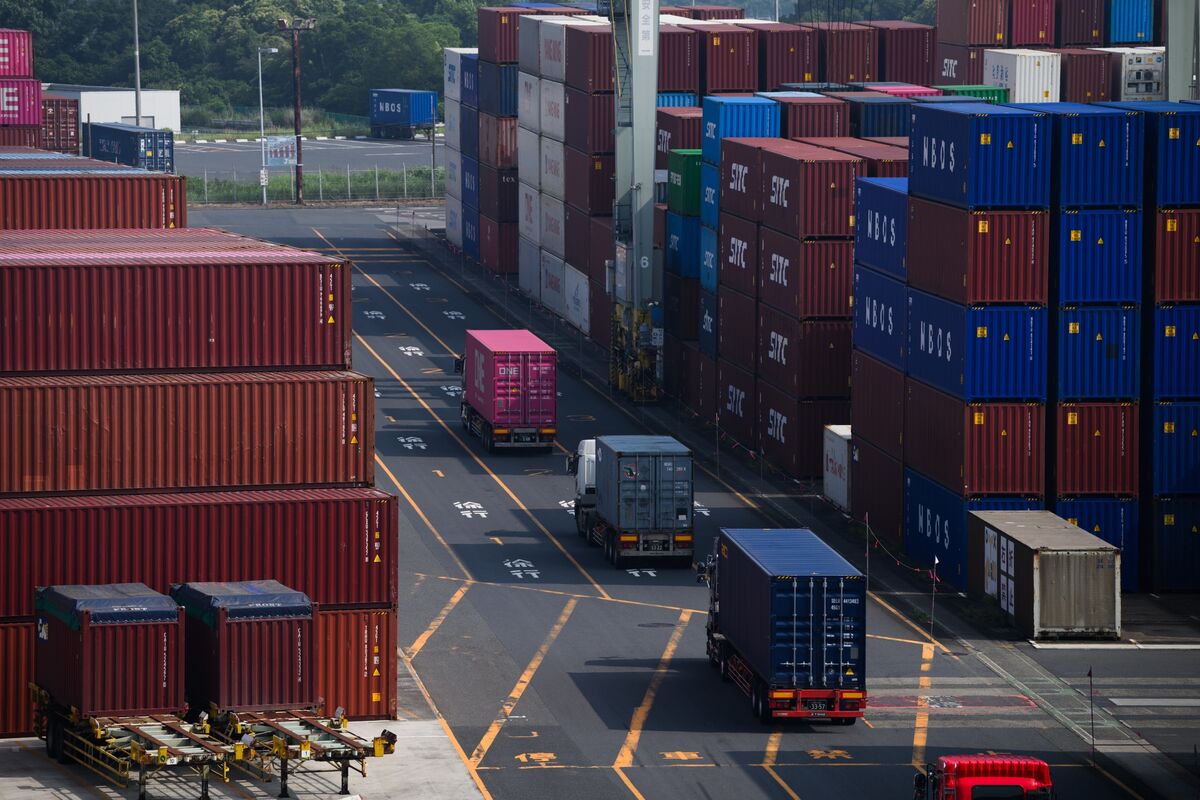

Implications for Economy and Markets

Expect continued gradual hikes if projections hold, balancing growth and price stability[2]. Lower borrowing costs remain vital for Japan's debt-laden fiscal position, yet this shift could strengthen the yen and influence global markets. Investors watch closely as Japan normalizes policy after years of deflationary struggles[1].

About the People Mentioned

Sanae Takaichi

Sanae Takaichi is a Japanese politician of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) who became Japan’s first female prime minister after winning the LDP leadership and being elected by the National Diet in 2025[2][3]. She was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1993 and has held multiple cabinet posts, notably Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications and Minister of State for Economic Security[5][3]. Takaichi is widely described as a conservative and a protégé of former prime minister Shinzō Abe, advocating traditionalist cultural policies, stronger defence and economic-security measures, and limits on immigration[5][3]. Her tenure as a senior minister included controversial moves such as seeking greater government influence over public broadcasting and visiting the Yasukuni Shrine while in office[5]. After several attempts at party leadership, she secured the LDP presidency in 2025 and led a minority government formed with the Japan Innovation Party amid a fractured Diet and the end of the long-standing LDP–Kōmeitō alliance[2][3]. Key challenges cited for her government include restoring public trust after LDP funding scandals, addressing Japan’s demographic decline and low growth, high public debt, inflation and wage issues, and navigating a tense regional security environment involving China and North Korea[2][3]. Analysts note her policy priorities include expansionary fiscal measures, tighter control over monetary policy levers, and strengthening the U.S.–Japan alliance and economic-security ties[2][5]. Takaichi’s rise is significant both for breaking gender barriers in Japanese national leadership and for shifting the LDP toward more conservative, security-focused policies during a period of domestic political realignment[3][5].

About the Organizations Mentioned

Bank of Japan

## Overview The Bank of Japan (BoJ), established in 1882, is the nation’s central bank and the sole issuer of the Japanese yen[1][6][7]. Its primary missions are to maintain price stability and ensure the stability of the financial system, roles it fulfills through monetary policy, currency issuance, and oversight of financial institutions[5]. The BoJ is headquartered in Tokyo and plays a central role in shaping Japan’s economic landscape, influencing everything from inflation and interest rates to foreign exchange markets[5][7]. ## History The BoJ was founded to unify and stabilize Japan’s previously fragmented monetary system, which was plagued by numerous private banks issuing their own currencies[3]. Modeled after European central banks, the BoJ gained a monopoly on money supply control in 1884 and began issuing banknotes in 1885[1]. Its early years were marked by Japan’s adoption of the gold standard in 1897 and the gradual consolidation of national currency issuance[1]. The bank underwent significant reorganization during the 20th century, especially after World War II, when its functions were briefly suspended during the Allied occupation[1][4]. The 1942 and 1949 reforms redefined its structure, including the establishment of the Policy Board[2]. For much of the post-war period, the BoJ relied on “window guidance” credit controls, which were later criticized for contributing to the asset bubble of the 1980s[1]. The 1997 Bank of Japan Act granted the BoJ greater independence while emphasizing collaboration with the government[1][2]. ## Key Achievements The BoJ has navigated numerous economic challenges, including the oil shocks of the 1970s, the asset bubble and subsequent bust of the late 1980s and 1990s, and the prolonged deflationary period that followed[3][4]. In response, it pioneered unconventional monetary policies, such as the